Do We Have a Moral Obligation to Provide Brain Wellness Training?

Following an extensive review of the data, the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention and Care challenged the medical community and society with the following conclusion:

“…(G)iving people information about how to prevent or treat dementia is an essential first step but is not enough. There is a responsibility, not just as professionals but as a society, to implement this evidence into interventions that are widely and effectively used… Interventions have to be accessible, sustainable, and, if possible, enjoyable or they will be unused.”

As a longstanding expert in brain health, I believe we have a moral obligation to empower everyone to take charge of their cognitive wellness. In the history of healthcare there are turning points when we shift from suggestion to prescription – think, for example, about vaccinations or heart health promotion. A myriad of factors indicate that we have reached such a point, and that it is time to take a more proactive approach to brain health. The Lancet Commission statement is a very welcome invitation to move brain health to the forefront of our health promotion initiatives, for many reasons, among them:

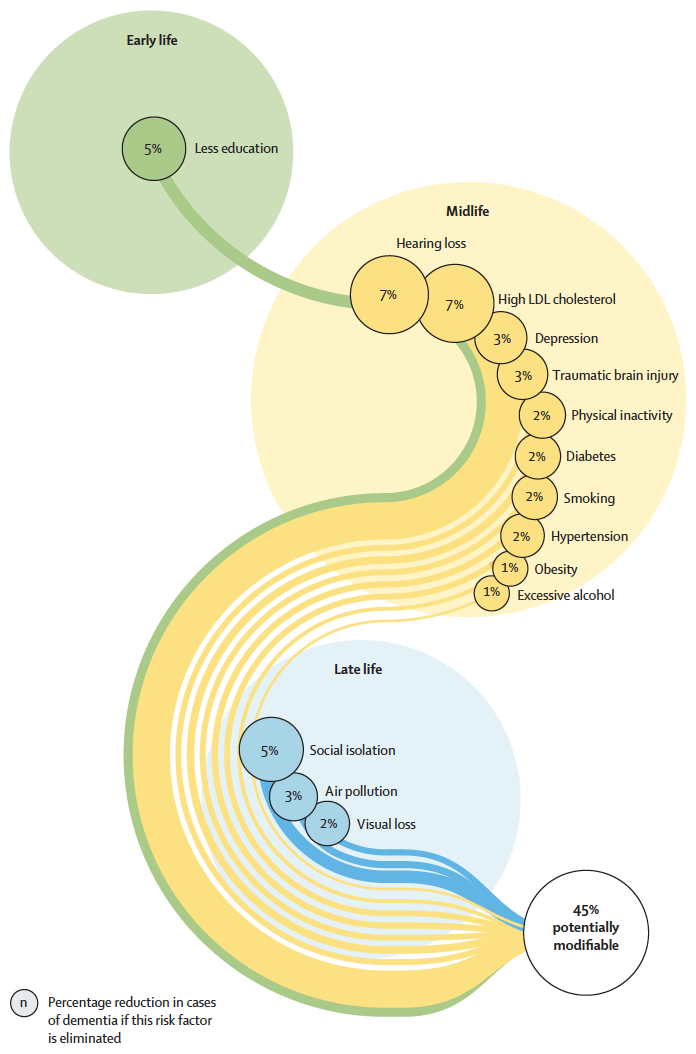

The Science is There. Over the past three decades, we have experienced rapid-fire growth in our scientific knowledge about dementia prevention. We have evidence from large, well-designed observational and interventional studies that lifestyle behaviors can significantly impact our dementia risk. As the Lancet Commission found, these behaviors range from ones that must be implemented on both a societal level, such as childhood education and social isolation in older age, to personal behavior, such as physical activity and managing hearing loss. The time is ripe for interventions that engage us in brain healthy lifestyles and promote the full range of what keeps our minds sharp and reduces our risk for serious memory loss.

In addition, we are beginning to see more evidence that specific lifestyle interventions, such as physical exercise and meditation, may slow decline in those diagnosed with memory disorders. Leaders in the field, such as Dr. Ronald Petersen, have in fact recently suggested physical activity be prescribed to those with early memory loss.

Recent small studies even suggest that targeted training may even improve cognitive performance in individuals with early memory loss. While the evidence may be early, the potential benefits for most of these interventions, which are often wellness-based and economical, seem to outweigh any inherent risk.

Dementia is a Crisis We Can’t Ignore. Dementia is a worldwide societal crisis. On a global basis, over 45 million people carry a diagnosis of dementia, and the World Health Organization has declared dementia a public health priority. However, the impact is not only medical: The 2015 World Alzheimer’s Report concluded that the worldwide economic drag of the disease is so high that if dementia care were a country, it would be the 18th largest economy in the world. With so many at risk, we can no longer afford to be passive or hesitant in our approach to reducing risk or providing better care to those affected by memory loss.

In addition, dementia is a personal crisis for far too many. It is a devastating disease, not only for the affected individual but for their family, friends and community. Giving relief in any degree that may slow decline, support a better quality of life and help all affected is a morally compelling reason to re-envision and retool what we do in brain wellness across the cognitive continuum.

We Have the Tools to do Better. It is time for the healthcare field to rethink what we do to promote better brain health. As the Lancet Commission researchers note, “giving people information simply is no longer enough.” We must move beyond white papers to meaningful, robust programs that empower people to take better care of their brains. We have the tools to develop innovative, out-of-the-box methods that provide the means to lower risk, improve performance, and live better in the face of disease. Methodologies such as gamification, social-based brain training and experiential learning all offer new and exciting ways to fully engage in all the science shows we need to do to promote cognitive fitness. In memory care, we should continue to explore new pathways towards equal opportunity for cognitive engagement and meaningful, vibrant connections across the cognitive continuum, breaking down the barriers modeled on medical constructs, and taking advantage of technological advances to manage concerns around safety and care. Finally, whatever else, we need to make brain health fun – not childish, not over-simplified, but engaging, challenging, compelling and exciting.

We are at the point in the history of brain health where we have the evidence and need, both professionally and as a society, to empower everyone to take better care of our brains. The moral burden is on us to act – the only question is how we will rise to the challenge.